Currently: I’m taking a breather after putting my kids to bed

Reading: Curandera by Irenosen Okojie

Watching: The Con on Disney+ (are you starting to notice a pattern?)

Listening: ‘Left Right’ by Keys The Prince

Thinking: Keys The Prince is actually making the soundtrack to my life as a British Nigerian. The blend of Yorùbá musical culture, UK rap, Jamaican Patois-inflected pronunciations (listen to ‘Ballaz’), Gospel influences (listen to ‘E Se Pt 2’) …I have been playing nothing else for the last few days.

Content note: This post talks about death and grief.

We used to steal things, but don’t all teenagers at one point or another? We’re like toddlers testing out the boundaries of our world, but instead of diving head first off of sofas, we’re seeing how many KitKat Chunkys can fit down the sleeve of our school jumpers before the bored security guard in WHSmith catches us.

I had friends who stole makeup from Woolworths, but that never appealed to me because the pastel pinks and blues of mid-noughties tweenage trends always looked ashy on my skin. But Claire’s Accessories?! That was a tiny shop full of treasure.

There was a particular skill to popping off earrings from their cardboard holders; there was a way to pocket necklaces and rings with just the briefest flick of the wrist. It was with great irony that a couple of years later, my first job would be as a sales assistant at Claire’s.

I was working at the Claire’s on Oxford Street the one and only time I caught school girls stealing. I wasn’t even paying attention to them, but I noticed a strange bulge in the golf umbrella one of them was carrying.

As they made their way out of the shop, I called them back and held my hand out for the umbrella. I remember I was trembling slightly as I unloaded jewellery from its nylon folds. I hate confrontation.

I was probably meant to take them out the back, write down their details, ban them from the shop and put the fear of God into them a little bit, but instead, I handed them back their umbrella and told them they could go. I didn’t even tell my manager.

*

So much of getting older is becoming the thing you once fought against – or if that’s too dramatic a characterisation, then at least the thing you were in opposition to.

Raising children is like seeing fleeting glimpses of the childhood version of yourself. The flashes of defiance, the exasperating shortsightedness, the attitude that being a kid is the hardest thing in the world and secretly believing that you are smarter than all the grown ups around you – if you are honest, the resemblance will be uncanny.

I was talking with a friend about teenagers we know and how they are so annoying in the inevitable way that teenagers just are.

“We were probably just as bad though,” I laughed with a shrug.

My friend replied: “No, I know for a fact I was worse.”

*

There is a recurring pattern I notice in the main characters I write. Bubbling away beneath the main plot, is the tension they have with their mothers. Glory and Celeste, Mimi and Bísọ́lá, Abi and Marie; the push and pull of a daughter reaching for self actualisation in whatever form they feel necessary, and feeling like their mother is obstinately in the way.

It is never a conscious addition, but it always feels true, as does the way that, as the novel progresses, Glory and Mimi in particular, begin to reflect sides of their mothers to different degrees. It’s inevitable that the person who raises you will leave fingerprints of their character, but as these revelations surface over the course of my narratives, I am always amused and delighted.

The next pattern, which is very much intentional, is that by the end of my time with these young women, I am writing them towards some kind of reconciliation with their mothers. In real life, I know that’s not always true or always possible, but as long as I can shape the universes my girls live within, that is of supreme importance to me.

*

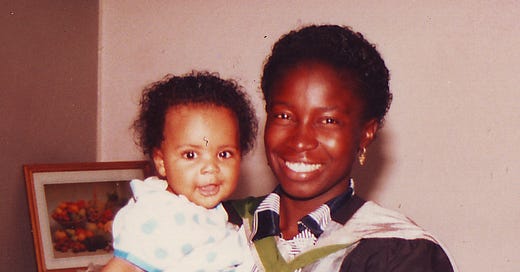

When my mother died, we weren’t beefing, but we weren’t as close as we should have been. The whats and wherefores are no one’s business, but for a long time all I felt was anger. Of course, mainly at myself.

Throwing myself into the admin associated with someone’s death was an easy way to keep calm and carry on and it also felt like a productive avenue to channel all my anger and grief. Tangible outcomes and a depleting to-do tasted like penance for whatever ways I felt I had fallen short as a daughter.

On the day of her funeral, the Wednesday before Mother’s Day, I didn’t cry once. This is something that I’m pretty sure she would have respected, approving of me playing the dutiful host, ensuring everyone was well-fed with food packed into Tupperware to take home afterwards.

Maybe I played this role too well, as someone saw that day as the perfect time to say, “You are the mother now. Your brother and dad need you.” My mask of togetherness faltered slightly, I could feel a flash of anger rising, but instead I stretched a wan smile across my face and nodded absently, looking past my advisor.

*

There are things about my mother that I was simply too young to appreciate and growing older is understanding her more in her absence. It’s easy to pinpoint what I’ve learned from her, but the ways I feel myself becoming her still take me by surprise. There are times when my decisions are guided solely by doing what she would have done, and then there are the times that my conclusions are shaped in complete opposition.

As a teenager, I resented her for being away from home so often. She was working across Europe on various contracts when I wanted her there to sew sequins onto a leotard for a dance performance. I played competitive netball to County level and even went to England Development Camp, but I don’t remember her attending a single one of my netball matches. But maybe this is uncharitable.

Still, with these instances seared into my emotional memory, for the most part, my work has been shaped to fit around my children – to the point they seem to forget that I actually have a job and other obligations besides taking them to football and nagging them to get ready for school every morning.

This is a conscious decision, so I have no regrets, and I know my kids are proud of me when they are recommending my novels to parents chaperoning their school trips or when they swipe right on my phone to see a picture of me sitting in the BBC 1Xtra studio and exclaim in excitement.

But did my mom know that I was proud of her? I hope so.

*

I dream about her most nights.

At first, the dreams were scary and guilt-ridden, zombie versions of her resurrected to give me stern warnings that I couldn’t understand. The dreams would have me passing incidents from my waking life under an anxious microscope, trying to connect dots that may or may not be there.

Then the dreams got so mundane, they began to feel like memories. I’d wake up confused and disorientated, trying to separate wish from memory from dream from reality. I’d wake up thinking, “Did I just have a dream that my mom had died?” before the realisation would seep in that no, no… she really was dead.

My understanding of heaven doesn’t convince me that she is watching over me. I think heaven is way too interesting and joyous to even fathom watching the banal misery of your loved ones left behind. Our ancestors are gone, all we have is our memories and the bittersweet ache of love, and honestly that’s good enough for me.

Now, when I dream about her, it’s just an opportunity to spend time – definitely not the same, but close enough to provide some solace. And while I don’t believe it’s really her that I’m sitting with at a kitchen table or riding next to in a car going to who knows where, I still wake with the same thought every time: “Thanks, Mom. It was nice to see you again.”

Hibernation season approaches, but I will be at Tottenham Literature Festival this weekend for an expansive and energising conversation with Irenosen Okojie about the Black Imagination, and I’ll be at Guildford Library at the end of the month for BASK Book Club.

What a beautiful and profound read😍

‘There is a recurring pattern I notice in the main characters I write. Bubbling away beneath the main plot, is the tension they have with their mothers’. This is what I just love about your work. It’s been so healing to read and use as a vehicle to contemplate and come to new understandings of my own mum. Hope and Glory was so healing for me. Reading all that we’ve got as moving too for similar reasons. Becoming a parent, ahhh it makes so much sense! It’s given me a lot of grace for my mum and a lead to lot of frustration, grief and re-parenting.