Currently: Sitting in front of an open window and a rotating fan

Reading: The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan

Watching: Abbott Elementary…again…holding vigil for the next season

Listening: Hot Money: Agent of Chaos, a podcast by Financial Times (I have a tenuous personal connection the Wirecard scandal that means I’m forever obsessed with it)

Thinking: “It’s been a long time, I shouldn’t have left you, without a dope beat to step to, step to, step to…”

“I am torn between the fear of not being recognised and not recognising anything.” – Dahomey, directed by Mati Diop, 2024

“Your mom said you wanted to wear native.”

It was half question, half statement, delivered with a small amused smile by my older cousin.

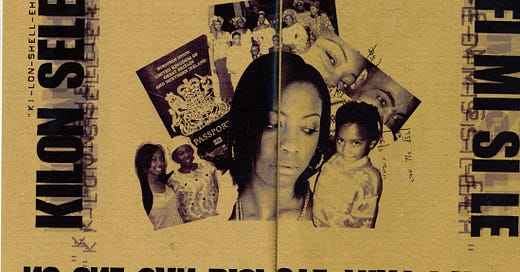

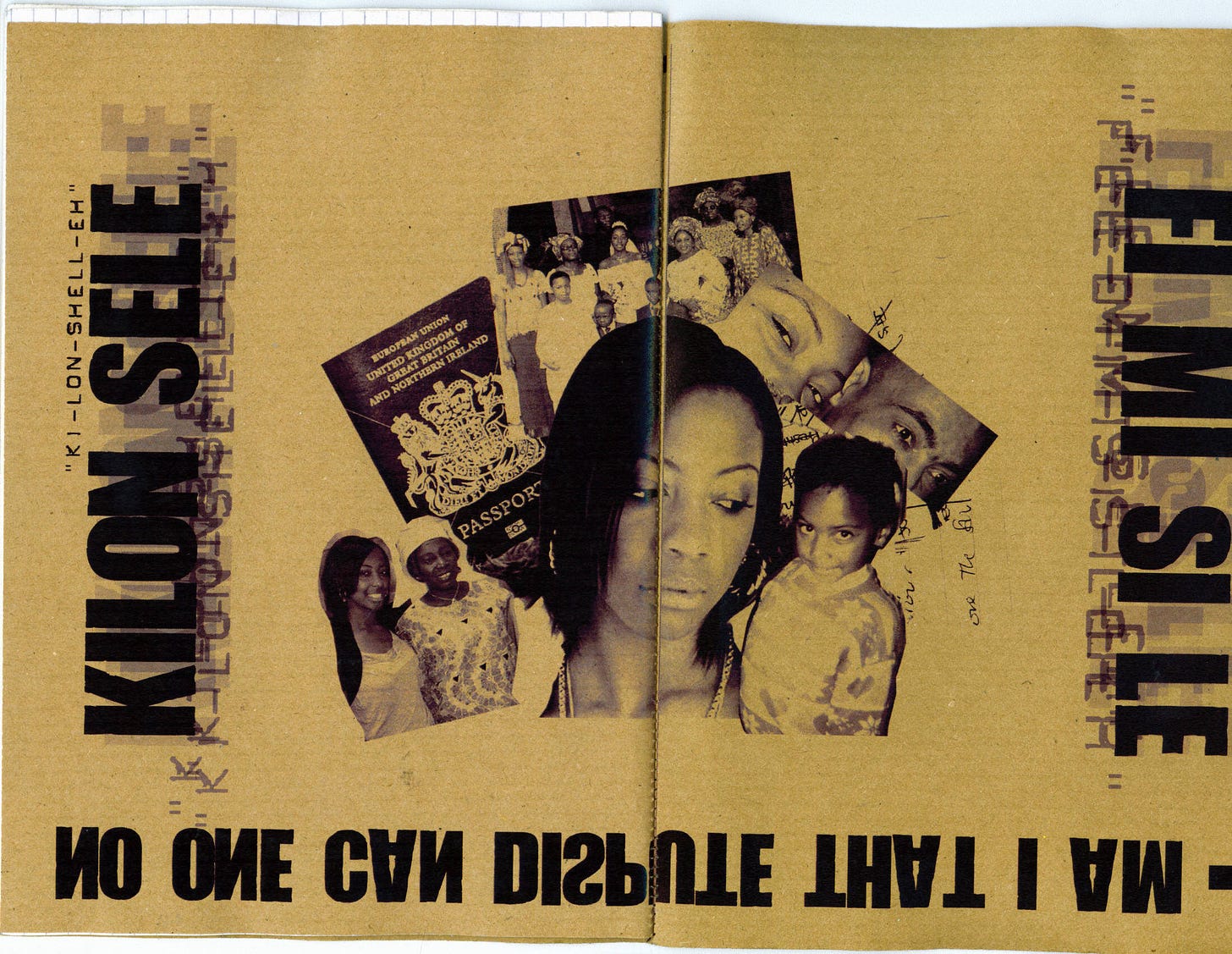

I was at her university graduation with my mom. We had driven down from Birmingham that afternoon and I had asked my mom why her sister, my Auntie B, had brought asọ-ẹbí for her – cranberry red and light pink aṣọ òkè – and not for me. My mother had answered with that same amused smile, a polite way of asking the question that remained unuttered – “...but why?”

Her failure to understand why I might want to wear asọ-ẹbí and feel properly included in the celebrations frustrated me, and my mood was slightly sour for the rest of the day. In the pictures, I’m wearing an awful acid green cotton top and dark cropped trousers, the closest thing to “graduation-appropriate” I had in my wardrobe. I don’t quite smile into the camera, more a side-eye and a grimace; a clenched jaw and slightly upturned lips.

My family’s harmless rebuffs had me internally revisiting emotions that first surfaced as a 10-year-old in Auntie B’s Lagos apartment. My mom and her siblings were together for the first time in maybe a decade or more, rapid-fire Yorùbá flying around the living room. My mom laughed brightly, showing all her teeth in a way that I rarely saw her do in England and I wanted in on the banter.

“I want to learn Yorùbá,” I told her.

“Why do you want to learn Yorùbá?” she responded, the same smile with averted eyes like I was asking a childish question.

I now have the language to describe the way I felt in those moments as a teenager and as a child. It was like being told I had no right to possess what I was seeking; like it was ludicrous to think that I had any ownership over Yorùbá language or culture because I was and would always be an outsider.

*

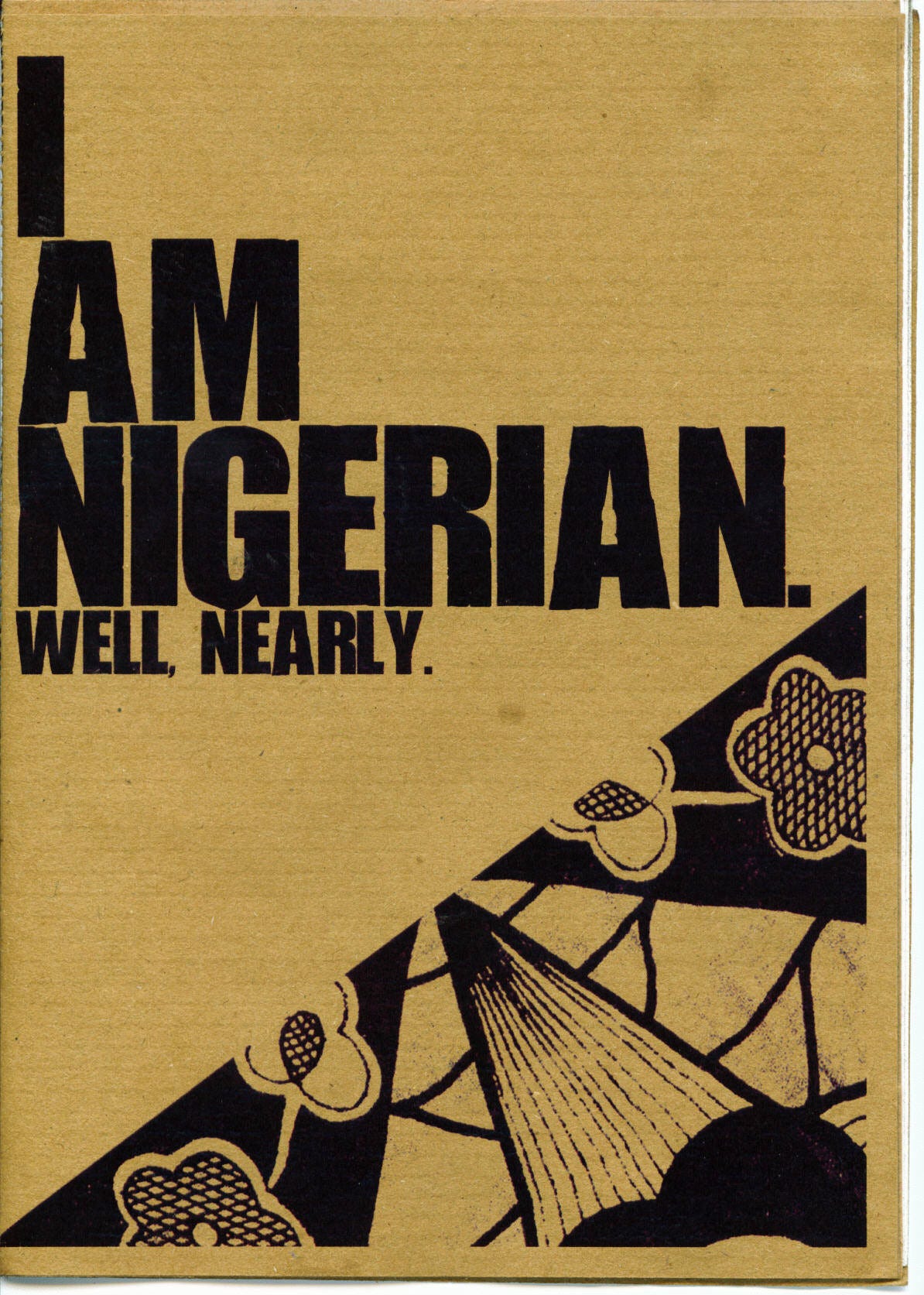

I’m not racially ambiguous by any stretch of the imagination, but I have made peace with the fact that I am ‘ethnically ambiguous’ – whatever that means.

When revealing my Nigerian heritage I am most often told that I look ‘Caribbean’ – Jamaican or St. Lucian are the recurring islands if people take time to be specific. But I’ve also been told I could pass for Colombian or Brazilian (although, given the racial history, couldn’t almost anyone?) and if I wasn’t as tall as I was, maybe South African…

“Oh, so you’re Nigerian! Igbo, right?”

Nope, wrong again.

*

*

One of the Notting Hill Carnivals I attended when I was still living in Birmingham, a guy approached me in the dying embers of Bank Holiday Monday.

After a few minutes of conversation he asked, “You from Yard [Jamaica, but the inference being you came to the UK relatively recently]?”

“Nah, I’m from Birmingham.”

“Rah, you sound like you’re from Yard!”

When I watch myself in old pixelated videos from the era of Samsung E800s and the Sony Ericsson W810i (the Walkman one), I’m always taken aback. My Birmingham accent is so much stronger, yes, but it is also thickly peppered with Jamaican Patois like some personal creole. The first time I re-watched old videos, I wondered if I was exaggerating for effect.

But then I remember having to take my brother to the barbershop, sitting, waiting and eavesdropping on the high-speed Patois ricocheting around my head. I would piece together intimate personal details about people I didn’t know and try to stifle giggles as the barbers roasted each other.

As a teenager, I rarely stumbled when someone assumed I was Jamaican and addressed me in Patois, so I shouldn’t be shocked at the ease with which phrases and idioms slide off my tongue in those videos. I think I’m just more surprised that I forgot that this is how I sounded once upon a time.

*

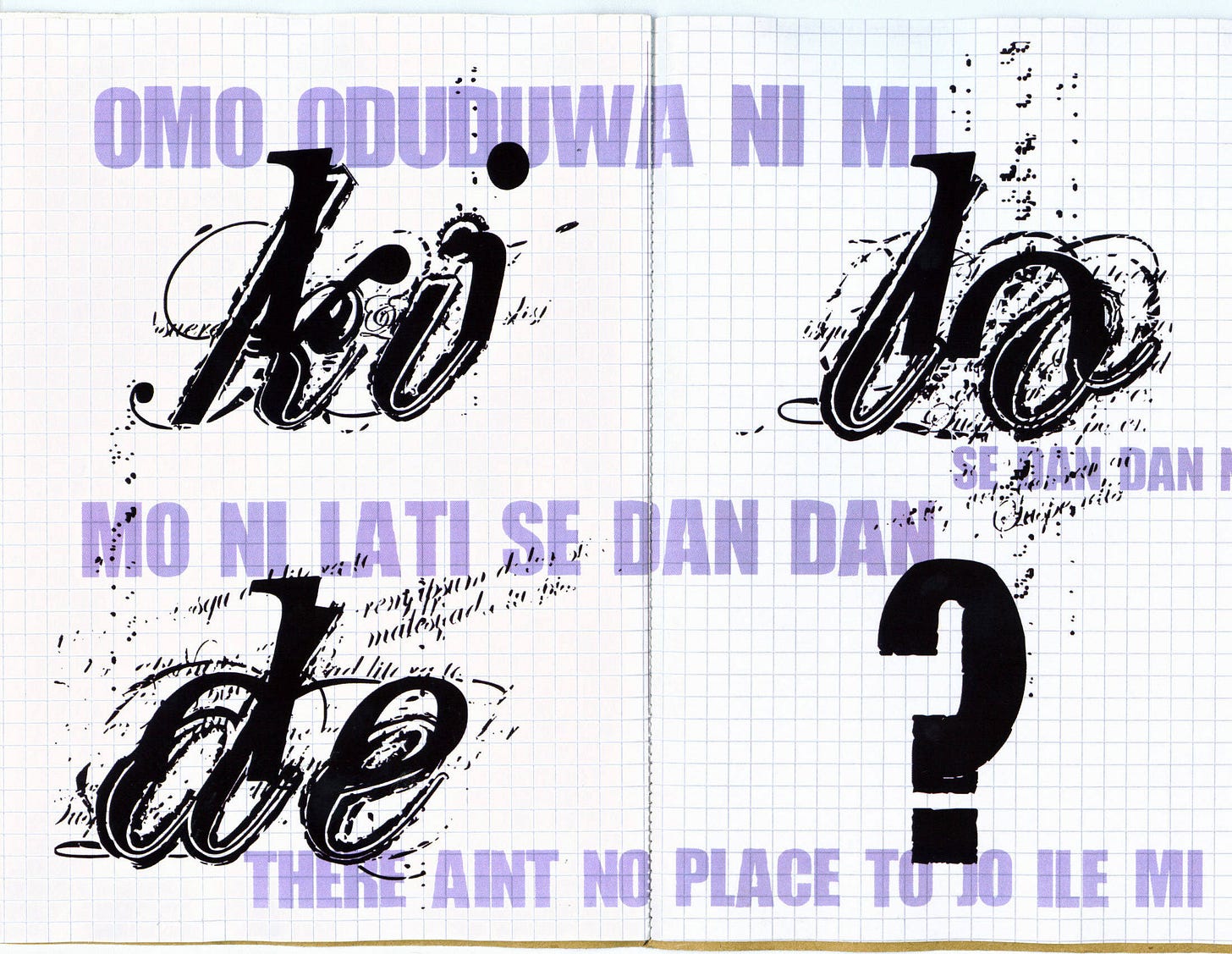

About a year after my mom died, I decided to start Yorùbá lessons. I didn’t pretend that I knew anything about anything, so I started as an absolute beginner, learning how to sound out the alphabet and greet for the appropriate time of day. Languages are my thing, so everything was clicking pretty easily, but what is knowing a language in your head if you cannot speak it?

As I tried to mould the tonal sounds in my mouth, my tongue felt too thick and lazy. Each time I opened my mouth to speak in class, I felt a crippling fear of embarrassment clog my throat and then I’d stop committing. Syllables started to slide around into some half-hearted, hybrid accent, shame trying to hide behind nonchalance.

The same shame told me that this should be easier – this was my culture for goodness sake! It should be in my blood! The cycle of struggle and embarrassment felt like a verdict on my authenticity, something that has been consistently up for (internal) debate since the first time I landed back in Nigeria and a woman in the market called me ‘òyìnbó’.

*

On that same trip, we attended a family wedding. That day, I was dressed in asọ-ẹbí, a dark purple and lilac aṣọ òkè dress and head tie. We posed for pictures that would appear in Ovation magazine and I ate chin chin until my stomach was fit to burst.

At one point, I left the main celebration hall to go and find the bathroom. When I came out of the toilet stall, there was an older woman struggling with the door to the women’s bathroom. She spoke to me in fast, frustrated Yorùbá, gesturing at the door.

I had no idea what she said but it was easy to conclude that the door was stuck. Wordlessly, I approached it, jiggled the handle a little, tugged harder and it popped open. She grunted her thanks, and I followed her out of the toilets, trying to tamp down the smile on my face.

Her assumption that I could speak Yorùbá meant so much to me at that moment.

*

Growing up, my mom used to eat ground rice with her stews. Where we lived at the time, pounded yam, ẹ̀bà and àmàlà were not freely available, unless a relative flew in with packets of garri or yam powder stuffed in their suitcase.

She would buy the ground rice from South Asian grocery shops, mixing the grainy white flour with hot water into cloud-like tufts. I forgot all about this until I was sitting in Enish, and a young black man entered with his Arab friend.

They were seated at the table to my right and I overheard as the young man started gassing up Nigerian food to his companion. It seemed that this was going to be an introduction to Nigerian cuisine, and the young Nigerian was very excited to curate the experience.

When the server came to take their order, he asked for ogbono soup with ground rice. The server said they didn’t have it.

“You don’t have ground rice?!” the young guy asked, incredulous. “Have you run out or what?”

“No, it’s not something we serve at all. It’s not like a traditional Nigerian dish – it’s more a Nigerian British thing.”

“Oh, OK, we’ll just take the ogbono soup and then we’ll have jollof rice.”

“Just ogbono soup and jollof rice?” the server repeated, heavy emphasis on each word.

“Yeah, yeah…that should be calm.” Then turning to his friend, the young guy excitedly assured him, “you’re gonna love this, bro!”

All I could think was… ogbono soup and jollof rice?! I wanted to save the unsuspecting friend from such an abomination of a combination.

For further context, this was hot on the heels of another group of younger guys who had been sat on my left and agreed to one another that they would all have “j-rice”.

“J-rice?!” I internally shrieked. It just felt wrong, disrespectful, too careless. I sat there eating my plantain and beans feeling like a proper auntie, despairing the trajectory of the youth.

(Truth be told, the “j rice” rebrand would have floated with younger me, tired of coming home to rice and stew instead of pizza and nuggets like all my school friends.)

*

*

In the first year that I lived in London, Auntie B was visiting the UK and came to stay with me. She returned from Peckham one day with a big bag of rice, tins of plum tomatoes and kidney beans, fresh vegetables and meat and told me that she was going to teach me how to cook a few key Nigerian dishes.

She taught me how to make pepper soup, jollof rice and moin-moin in that time-honoured way of no measurements, just an ancestral knowledge. After she left, I was excited to give it a spin on my own.

The pepper soup was delicious, the moin-moin was passable and the jollof rice was an absolute shambles – inedible. I tried cooking jollof twice more before I decided that I actually didn’t even like jollof rice that much and swore off it completely.

What I didn’t say was that it was too hard to do; I was too inexperienced to judge the correct ratio of water to rice, whether I started with parboiled rice or raw. Shame, again, was my sous-chef as I believed that I should just know how to cook it, it was my cultural inheritance and it should just flow from my fingertips by birthright.

When I lived with my paternal grandmother years later, she made a big pot of ogbono soup, leaving the leftovers on the stove instead of packing it into Tupperware and storing in the fridge.

“Every morning you have to heat it up and stir to kill the bacteria, that’s what we used to do when we didn’t have fridges,” she said, recalling her childhood in Kabba. She continued to draw the wooden spoon through the viscous soup, singing in Yorùbá as she stirred.

“Do you know what that means?” she asked, knowing full well I didn’t. “It means ‘when I grow up, I will be a first wife, I won’t be a second wife, stirring soup’!”

She cackled then, her eyes bright and full of mischief behind her glasses.

*

After news of my mom’s passing spread, some old family friends came to visit. My oldest son was a toddler, eager to show these friendly strangers all of his favourite things. He brought down the book that we had been reading on repeat, ‘Mayowa and the Masquerades’ by Lola Shoneyin, and handed it to one of the visitors.

“Masquerades?! Seriously?!” he asked in alarm as he read the title, unable to veil the shock and disapproval in his voice.

Afterwards, my dad explained to me how for the most very-Christian of Yorùbá people, traditional masquerades were essentially witchcraft – out of bounds, completely unacceptable.

“Where does culture start and stop, though?” I argued with him. “Yorùbá culture is extremely deferential to elders, in the way you speak, even in the order that food is served, but can’t you completely divorce that from the history of ancestor veneration [which is what masquerades allude to]?

“I’m just trying to understand where I come from, the philosophy and the way that Yorùbá culture understands the world. I’m not saying that I’m going to start visiting a babaláwo [Ifà high priest, or more commonly, a ‘witchdoctor’], but it’s all connected. I’m just trying to understand how it all fits together.”

*

I stopped Yorùbá classes after a while, feeling like I wasn’t really progressing when I was unable to get over the self-consciousness of speaking in a group setting.

I scrolled past adverts for Yorùbá mixers on TikTok promising that people of all abilities were welcome. I skipped past videos from other Yorùbá descendents in the diaspora promising that the quickest way to speak the language was to just speak the language – errors and all. I watched videos of Ifà adherents in Cuba and Brazil, jealous of the way that these folks, however many generations removed from Yorùbáland thanks to slavery and colonisation, could fluently sing Yorùbá venerations to their personal òrìṣà.

Then I started watching afrobeats translation videos, Yorùbá speakers miming along to Asake songs with the English translations floating above their heads. Then I started listening to the I Speak Yoruba Too podcast – starting from the beginning once again, learning about pronouns, tenses and all those small in between words like “this” and “that” in bitesize, 10 minute episodes.

It was then that I realised what my issue was. I needed to learn Yorùbá how I learned French and Spanish in school. I needed the grammatical breakdowns that bored other students, the tangents that explained how a phrase that didn’t translate directly into English came to be. I needed to understand the mechanics and the philosophy of the language, not just collecting vocabulary.

I started looking up one-on-one lessons, knowing that a six-week group course was not going to cut it anymore, but my disposable income and the cost of the lessons were not aligning. Then my cousin told me that she was learning Hausa with a one-on-one tutor she found online.

*

*

My first lesson with my Yorùbá tutor went something like this:

She appeared on my screen, her energy radiating from the grin on her face and she immediately addressed me in Yorùbá. I stuttered, mumbled, then cleared my throat and replied “Hello!” sounding more English than I had ever done in my entire life.

She then asked me why I wanted to learn Yorùbá and I sheepishly relayed my life story and family history, a logical explanation as to why I don’t speak a language that I should already know, before ending in a rush of breath that my mom had died a few years ago, and that made me want to speak it even more now.

She nodded and smiled. An awkward silence stretched out between us. “So tell me something else about yourself,” she coaxed and my mind went blank, feeling like I was on a first date and had nothing to offer as proof of my worthiness.

“OK, o! So you don’t want to know anything about me?” she teased breezily and then I hastily said, “Well, I can tell you why I wanted you to be my tutor!”

She smiled and inclined her head towards her camera, like, ‘OK, go on…’

“I saw that you’re doing your postgraduate studies in Yorùbá language and literature and because I love to understand the mechanics of a language and also I love literature as well, I thought we might have a similar way of seeing language.”

My tutor laughed, admitting that studying Yorùbá language and literature was one of those degrees that people thought, ‘Why are you studying that?’ but she loved it. We discussed her favourite Yorùbá authors and the kind of books that I read and then she launched into a lesson, starting with the Yorùbá alphabet.

“I know the alphabet already,” I said, a little too confidently because when she asked me to start reciting it, I hesitated too long, giggling nervously before stretching my jaw to form the letter “a” and instead pronouncing the letter “e”.

*

If you were eavesdropping on one of my 50 minute Yorùbá language lessons, you’d be forgiven for thinking I was getting vocal training.

My tutor will ask me to translate a word or a sentence into Yorùbá and then she’ll correct me where necessary, asking me what the tonal markers are for each syllable of the word I mispronounced.

I will reply, “do-do” or “mi-re” or “re-mi-do” and then she’ll ask me to repeat the word, my voice soaring and dipping to differentiate between each of the three àmì ohùn (do-do-re-do).

More often than not, my first attempt is too timid, my jaw too tight, my voice struggling to break out of the monotone constraints of native English.

Because in English, tone indicates sentiment: a question, a sarcastic remark, boredom. In Yorùbá tone is the language, the difference between oko, ọkọ, ọkọ̀ and ọkọ́ (farm, husband, car and hoe [for farming]); the difference between coming (wá) and being (wà).

Understanding that is understanding that the name “talking drum” is not metaphor, it is a statement of fact: the drum talks. It’s understanding why Yorùbá lyrics are so mesmerising when sung over music whether it’s jùjú (not to be confused with ‘juju’ – witchcraft), fújì or over an amapiano beat and it’s why people around the world are compelled to memorise lyrics with or without translation.

So it’s why I preface each Yorùbá lesson with a few vocal warm ups, exorcising the clicks in my jaw until the muscles feel limber and ready. Because the only way I’ll ever speak Yorùbá fluently is if I allow myself to sing… and there’s no space for shame when you’re singing.

This is far from an ad, but I found my tutor through Preply, and if you use my referral code to find your own language tutor (Yorùbá, French, Farsi, Mandarin or whatever…) you’ll get a 70% discount off your first introductory lesson and if you like it enough to continue, I will too 🙂

My second novel, All That We’ve Got, is now out in paperback from everywhere you get your paperbacks (bonus points for indie bookstores), and I’ll be stopping off at a few places this summer to talk about it and sign books:

15th July: The Heath Bookshop, Birmingham

19th July: The Wilde Foundation Writers Festival, London

26th July: Love Stories Etc Festival, Manchester

1st & 2nd August: The Black Ballad Weekender, London

I love this piece so much.

I love this — this part jumped out at me (a linguist and lover of sociolinguistics especially): “I needed to understand the mechanics and the philosophy of the language, not just collecting vocabulary.” Thank you for sharing a deeper insight into the connections language holds. ❤️