Currently: experimenting with audio voiceovers…think of this like mini podcasts…we’ll see how this goes…

Reading: Little Rot by Akwaeke Emezi

Watching: Fresh Off the Boat on Disney+

Listening: Mostly Lit podcast (welcome back, guys 🥲)

Thinking: am I being too greedy trying to squeeze in a third holiday this year? maybe the fact that I can’t really afford it is a sign…

Amongst the publicity for Amazon Studio’s thrilling adaption of Naomi Alderman’s novel, The Power, I saw one of the producers (I think) describe how powerful teenage girls are. I saw a similar sentiment expressed in reference to Eliza Clark’s haunting novel, Penance, and if you search “teenage girls” and “power” you’ll find feminist think pieces echoing much of the same with conviction.

The general conclusion seems to be: even though they don’t realise it, teenage girls are incredibly powerful. But I happen to feel the complete opposite.

When I was a teenager, I thought I was invincible. If I didn’t consciously believe it, it was suggested by the way I moved through the world. More than once, I ended up jumping in the back of a car that appeared from a darkened road as my friends and I hitchhiked back from parties in the middle of nowhere. Walking home after midnight one night, I once had to duck into an actual graveyard to hide after a white van drove past me twice, its driver looking me up and down and licking his lips.

Accompanying an older friend to a “link” with a guy she liked, I spent the evening hugging a cushion in the front room of a stranger’s flat on the 15th floor of a tower block, while a 21-year-old asked me inappropriate questions and promised to “wife” me when I turned 16.

The stories go on and on. I didn’t purposely seek out trouble, and, thanks be to God, trouble never found me in any serious way, but as an adult (and a mother) I am horrified at the knife’s edge I was dancing on, fully believing that should things go left I was somehow able to “handle it”.

But ignorance flows in the other direction as well. Risky hijinks aside, thinking back to who I was at 15, adult me had a particular idea about her and her innocence, that was thoroughly realigned when I cracked open my teenage diaries for research for writing 15-year-old Abi for my next novel, All That We’ve Got (out in July).

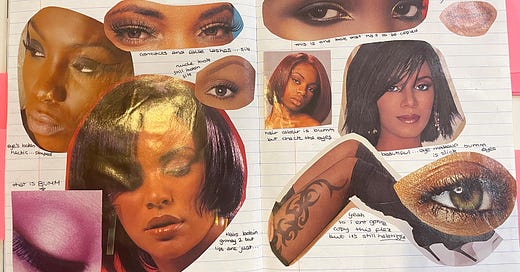

Amongst the collages of hairstyles, fashion and celebrities I had mild obsessions with, desire loomed large in the bubble writing and graffiti script I scrawled through the pages of my stolen exercise book. “Breaking up with boyfriend was hard, but needed to be done…obviously shows that some things are not meant to be…” I wrote, with the confidence of an older teenage protagonist in an American high school drama. “He’s a good lipser [kisser], dresser and dancer. He’s sweet and cute – a gentleman. Easy to talk to and a JOKER! He wanted to be my baby father, LOL!” I continued in another entry, heady infatuation emanating from the page.

Of course I cringe reading all of this back, but I’m also kind of impressed. The world was beginning to open up to me, its possibilities unfurling like a red carpet; knowing only a fraction of what I know about life now, I was ready to grab hold of it with two hands and a heap of hubris. But while general ignorance of the world had me jumping in headfirst without checking the depth, social interactions often left me painfully ill at ease.

If the intoxicating desire of teenagedom inspires excitement and yearning, remembering the acute self consciousness that plagued almost every social interaction makes my skin prickle with embarrassment all these years later. I often say that attending an all-girls school was psychological warfare, and though people laugh when I say it, I’m not joking. If teenage girls hold any power at all, first and foremost it is over each other. As an adult, I find that fascinating, even as my inner child cowers.

In my teenage diary there is a four-page account – basically a witness statement – of some drama that went down one day. It involved an ex-boyfriend, his ex-girlfriend, and a couple of girls from my school who had made friends with the ex as she went to a local college.

Reading back, I snigger at the dramatic flourish with which I recount events, full names (first and second name always) and side comments that I wrote during a Chemistry class. But what’s not as evident in the writing, although it is imprinted in my own memory, is how emotionally harrowing the whole experience was. When my school friend passed along the first message from the ex-girlfriend in an English lesson (the inciting incident), I was so upset I couldn’t control my emotions. When my teacher told me off, I threw my school jumper across the room (at her?!) and got a detention.

The back and forth between us two exes ended up merging with an existing, long-simmering resentment that was building between two other girls in my year. This bubbled over into a physical fight outside the newsagents which saw one girl modifying the placement of the other girl’s nose…with her fist. In the mutant way that rumours are maliciously conceived and spread, this escalated into a story spurred on by my nemesis about it being me as the one who got battered.

I remember how that whole saga felt and the way my stomach twisted at every potential confrontation. I remember the angry tears and the feeling of humiliation as the knife of spitefulness was twisted deeper by the self-proclaimed opponent. I was not mentally or emotionally equipped to beat her and the biggest irony was that at this point, I was not interested in my ex at all. My desire had long moved on to someone else.

So yes, in some respects teenage girls are powerful, but while feminists fantasise about them being able to electrocute those who would try and harm them (The Power), the reality is that the real leverage is held over girls as foolhardy, insecure and complicated as themselves (Penance).

Despite her missteps and short-sightedness, I don’t hold any ill-will towards teenage Jeni, neither is there any real “advice” I’d give her to do things differently. Sure, I could tell her to not take any of those boys seriously and stop trying to be everyone’s friend, but that advice makes little sense without the life experience that comes from not following it.

Similarly, telling her that she’s both ‘more powerful and more vulnerable’ than she can currently imagine seems part threat, part set up for the revelation of some hidden superpowers and a mission to save the world. So I think the only thing I’d actually want to tell her is she’s perfect: she’s everything she needs to be right now, for a life that she’s excited to live in the future and I love that for the both of us.

To see hear more from my teenage diary, head over to TikTok: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

Just under six weeks until All That We’ve Got is released into the world, you can still pre-order.